The Workshop

The long-abandoned Mycenae Tourist Pavilion is a typical architectural example of the post-war programme run by the Greek National Tourism Organisation (GNTO) to improve and modernise Greece's dilapidated tourist infrastructure.

It was completed in 1951 according to the plans of modernist architect Kimon Laskaris in order to make Argolis a powerful tourist destination.

Serving the nearby prehistoric site of Mycenae, the pavilion was to function as a crucial node in an integrated network of modern facilities that included the Epidaurus tourist pavilion (1950), the conversion of the fortress of Bourtzi into a guest house (1951), both designed by the same architect, the Xenia Amfitryon Hotel (1951 & 1956) by Kleon Krantonellis, the Xenia Acronafplia Hotel (1958) and the organised beach of Arvanitia (1962), designed by Ioannis Triantafyllidis and, later, the Nafplia Palace (1970-1975), designed by Thymios Papagiannis.

These facilities, built on natural sites of exceptional beauty and associated with the main archaeological sites, were to form the nucleus of the country's emerging tourist industry, attracting more and more Greek and foreign visitors. At the same time, the overtly modern architecture of the GNTO tourism facilities served as a vehicle for bringing Greece's remote communities into the modern world.

The Tourist Pavilion of Mycenae, located to the south of the prehistoric archaeological site, on a natural hill with a breathtaking view of the Argolid plain, is a discreet single-storey building of square plan, with a small semi-buried space that accommodated auxiliary uses.

It houses a T-shaped restaurant that extends through the building, leading to a porch to the south and a raised atrium, due to the slope, to the north.

The flat roof, offering panoramic views, is accessed by an integrated external staircase.

The floor plan evokes traditional closed arrangements around a central courtyard found throughout the Mediterranean, with additional subtle references to the Mycenaean megaron typology. The richly textured facades, which come alive with light, mitigate the severity and austerity of the single solid mass.

In keeping with GNTO's policy of small-scale spatial interventions that harmonise with the surrounding landscape, the pavilion's design is distinguished by its soft geometry and tempered modernism.

The piece de resistance of the restaurant's decoration was a large-scale portable mural by artist Nikos Nikolaos - with prehistoric iconography rendered in a modern style - suspended above the fireplace.

In Mycenae, the threshold between myth and history, the utopia of holidays and the reality of contemporary daily life, the place - that is, the totality of the immaterial and material elements that make up the complex identity of the natural and man-made landscape - is invaded with spatial folds that represent different temporalities: zones where time expands or is suspended.

The tourist pavilion in Mycenae is such an area.

Our workshop aimed to raise awareness both in the local community and among a wider audience of architects and artists about current aspects of cultural heritage and identity (local, supra-local, national, etc.) enhancement through the creative mediation of cultural memory.

In particular, our workshop used the material/spatial trace of the disused tourist pavilion as a vehicle to renegotiate lived or even imagined experiences and reactivate local memory. In this workshop, our students formulated pilot policies and developed conceptual protocols for the critical reactivation of collective memory and the integration of the tourist pavilion into contemporary community life.

Specifically, our students engaged in three successive but interconnected phases of reflection that included:

Memory mapping:

This phase concerns the kaleidoscopic recording of the local community's vivid memories and experiences of their 'relationship' with the tourist pavilion in the vein of typical oral history interviews. In addition, this phase involves the collection of personal memories (family photographs, etc.) in order to develop a dynamic cultural memory.

Finally, during this phase, the students had to carry out a cognitive mental mapping of the wider area, which included the dispersed archaeological site and the neighbouring villages of Mycenae and Fichtia.

The complex - like most state-run tourist facilities of the time - can be characterised as an example of an attempt at total design in the early 1950s, as it involved many interlocking levels of spatial intervention, such as the organic integration of the pavilion into a dynamic network of distant tourist facilities, its placement in a sensitive historical and natural environment, the design of a well-functioning restaurant, the synergy of art and architecture, and, finally, the design of furniture and other fittings in accordance with the overall visual identity of the Xenia network.

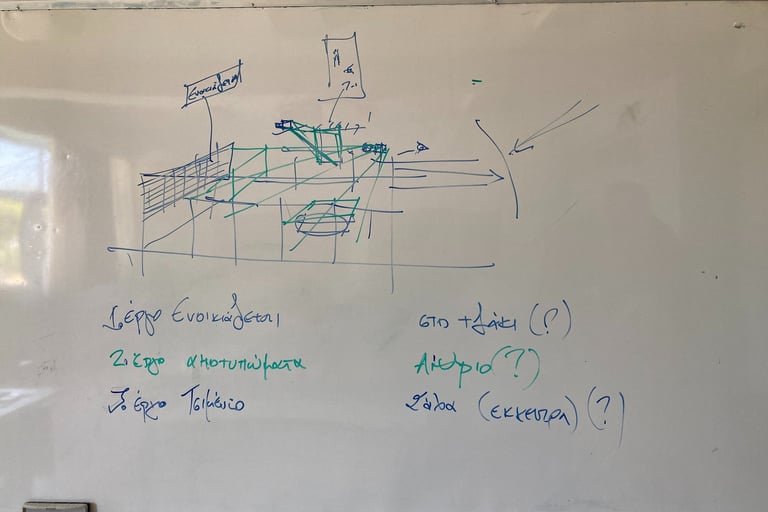

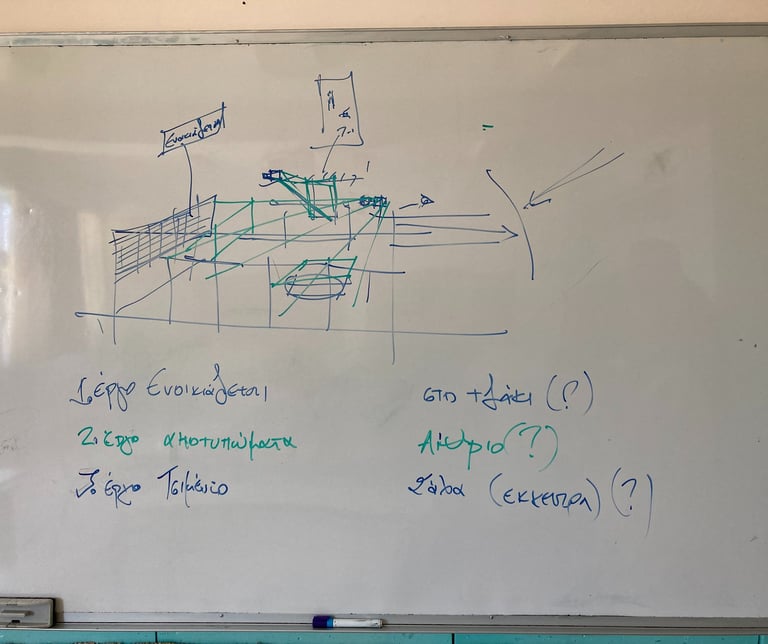

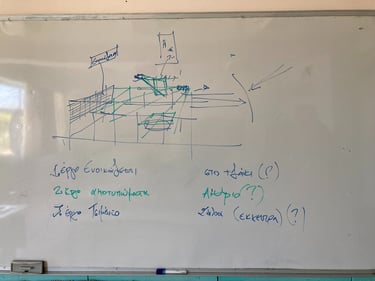

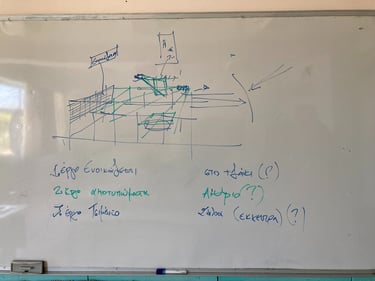

Transcription of memory and experience into spatial footprints:

This phase focused on the actual processing of the material accumulated in the previous phases in order to formulate pilot policies and develop hypothetical scenarios for the adaptive reuse and reintegration of the pavilion into the contemporary life of local communities.

This transcription was not exclusively design oriented. The processing of the data led to a variety of approaches - some more artistic, others involving locative media applications - which highlighted the potential of such policies.

Finally, topographical mapping of the workshop activities with web-based digital tools (Google Earth) provided a platform for dissemination of our work, as well as a 'digital diary' that can be used as a guide for future workshops.

Mapping the spatial experience:

This phase included the multimodal and multimedia mapping of the experience of walking through the site. The aim was to creatively and artistically document various routes and their corresponding 'conditions of passage', using the tourist pavilion as a starting point and reference.

This was an experiential exercise, where students had to record and interpret spatial elements such as routes, nodes, neighbourhoods, borders and other 'events' that give specific meaning to the experience of travelling through the historical, cultural and natural landscape of Mycenae.

Capturing the soundscape, an equally important environmental element, provided further opportunities for reflection.